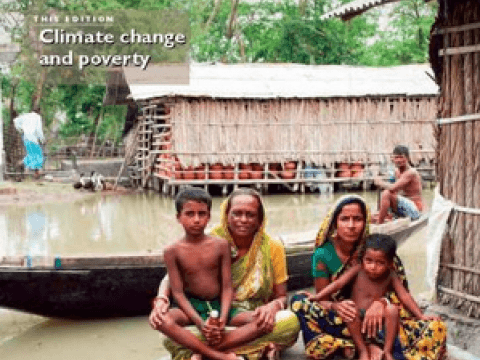

Global Future: Climate change and poverty

Télécharger

We are at a strange and dangerous point where most politicians want to look like they are “doing something” on climate change, but very few have the clarity and courage to do what actually needs to be done. I am reminded of a scene from the British comedy Yes Minister, in which the concept of “politicians’ logic” is explained: “Something must be done. This is something. Therefore we should do it.”

The problem is that it is not just any old “something” that needs to be done. As Bill Hare writes in this edition of Global Future, something very particular needs to be done to avert disaster: to have about a 50% chance of keeping warming below 2°C above pre-industrial levels, rich countries must reduce their emissions by around 25–40% below 1990 levels by 2020, and the biggest developing country emitters need to reduce their emissions below business-as-usual levels. To have a good chance of keeping warming under 2°C, and any chance of the safer 1.5°C, the Alliance of Small Island States and the Least Developed Countries have rightly emphasised that 45% cuts are more like what is needed, with more than 95% cuts below 1990 levels by 2050.

Very few of the rich countries are offering anything like these levels of cuts. By implication, these countries are content to risk 3°C, 4°C, or even 5°C of warming, but only a handful of politicians appear to grasp the extraordinary dangers inherent in these scenarios. As Will Steffen argues, our situation is grave and urgent action is required.

When we consider that about 5°C below pre-industrial temperatures produced the ice ages, 5°C above pre-industrial temperatures is frightening. Rather than a few more balmy summer evenings, we would experience temperatures not seen on Earth for tens of millions of years.

Several writers discuss the implications of our current path: Margareta Wahlström highlights the importance of disaster risk reduction for climate change adaptation; Chris Shore explains why climate change has such serious implications for the well-being of children; Alex Evans discusses the challenge of feeding nine billion people in the context of a warming world; Lydia Baker emphasises that climate change has critical child health

implications; Saleemul Huq and Muyeye Chambwera point out that for developing countries, pro-poor low-carbon growth is likely to have positive net benefits; my own article argues that the economic case for strong action on climate change is compelling; and in our closing reflection, Jim Ball emphasises that regardless of our views on the causes of climate change, we should respond to those suffering its consequences with the open-hearted generosity shown in Jesus’ story of the good Samaritan.

Unless decisive action is taken following Copenhagen, by 2100 our grandchildren are likely to know first-hand what the opposite of an ice age looks like. His Excellency Mohammed Nasheed, President of the island nation of the Maldives, asks poignantly whether our leaders are negotiating a global suicide pact or global survival pact: “Some might prefer us to suffer in silence but today we have decided to speak. And so I make

this pledge today: we will not die quietly.”

We do not choose the times we are born into. But we do choose how we will respond. How will our children and grandchildren remember us, if our generation proves incapable of rising to this challenge?