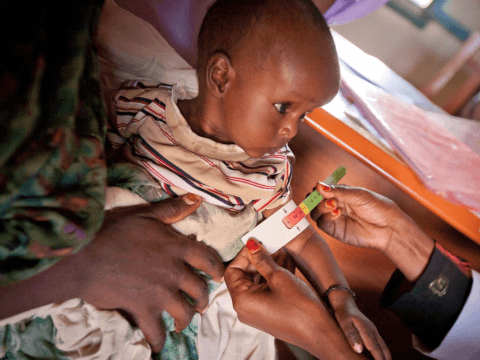

Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition

Addressing Wasting

Between 2010 and 2024, 88% of the 875,245 severely wasted children we treated made a full recovery.

Acute malnutrition, also known as ‘wasting’, increases the risk of serious illness or death. Globally, an estimated 45 million children under five years suffer from wasting, yet only 1 in 3 children receive the necessary treatment. Wasting occurs as a result of recent rapid weight loss or a failure to gain weight, often due to insufficient food intake or illness. Severe wasting is responsible for 1 in 5 deaths among children under 5, causing the loss of more than 1 million young lives each year, either directly through severe malnutrition or indirectly by weakening the immune system and increasing deaths in children suffering from common illnesses such as diarrhoea and pneumonia. Children with severe wasting are nearly 12 times more likely to die than well-nourished children. This issue is not limited to humanitarian crises, but is also prevalent in situations of chronic food insecurity and limited access to healthcare - 75% of wasted children do not live in humanitarian contexts. The world is off-track to meet global wasting targets, with 43% of countries showing insufficient progress, no improvement or worsening trends.

Since 2005, World Vision’s programmes have focused on the prevention and treatment of wasting, both in fragile and stable contexts in 35 countries, almost half of which are in the top 20 fragile states (Fragile States Index 2023). World Vision was an early adopter of the Community-based Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) model, which empowers communities to both identify and treat malnourished children.

In 2024, 180,774 children under five years of age were treated for wasting in CMAM programmes in 15 countries, keeping the vast majority from dying (>86% cure rate). (Data from 15 of the 20 countries implementing CMAM)

In addition, 40,627 pregnant and breastfeeding women in 7 countries received support through targeted supplementary feeding programmes.

Since 2010, more than 3.18 million women and children under five years of age have been treated through WV’s CMAM programmes in 35 countries.

Through conducting lives saved analysis, we estimate that 103,958 lives of children under 5 were saved through WV’s CMAM programming from 2010 to 2021.

World Vision contributes to various external technical and advocacy fora on CMAM and Wasting, including global research projects on wasting and through sharing data from our CMAM database. Recent engagements include WV executive leadership (represented by WV’s CEO, Andrew Morley) on the UNICEF-led Action Review Panel on Child Wasting. World Vision joined with partners to advocate for global action and accountability on wasting through the Global Action Plan on Wasting, and the Wasting Reset ahead of the UN Food Systems Summit and Nutrition for Growth Summit. An ambitious target of treating over 120,000 children with wasting per year was among WV’s commitments at the 2021 Nutrition for Growth Summit.

World Vision is a member of the UNICEF/WHO Technical Advisory Group on Wasting and Nutritional Oedema (Acute Malnutrition).