Germaphobe's Paradise

In the Paroumba community in Senegal, hygiene is part of the welcome

I’m a bit of a "germaphobe". And by “a bit,” I mean I’m the type of person who keeps a bottle of hand sanitizer in my pocket even though I have a larger bottle of it at my desk. I'm not proud of this, but for me, germ warfare has a different meaning.

So what happens when my photographer, Paul, and I arrive at a village in the Paroumba community in Senegal makes me realize I’ve come to a place of like-minded people.

The village members are singing and dancing, part of a characteristically warm Senegalese welcome. I’m a bit embarrassed—all this for me? Much too nice. What I expect next is a shaking of hands. Many hands. Hand after hand after hand. We’ve been visiting villages here for less than two days and I’ve already exchanged grips with at least 50 people. Each time, it’s different. Some are firm, others limp. Some are cold, others warm. Some are dry, others sweaty. Some are smooth, others rough. As a germaphobe, shaking hands is the hardest thing I do. I daydream about the sanitizer in my pocket.

But here in this village, the people don’t want to shake hands. At least not yet. They’re well aware of the germs that cover my hand like an invisible glove. They usher Paul and me to a handwashing station and give Paul a bar of soap. He’ll go first. In the meantime, I look around at everyone here to greet us. Their enthusiastic welcome feels like a homecoming.

Rouguiyatou

After I wash up, I shake hands with many people in the village. I’m fearless: These people care about their hygiene. They know that an easy way to prevent spreading germs and getting sick is to wash their hands, along with other simple and effective habits. But how do they know? Who told them?

Her name is Rouguiyatou. She’s 17 years old and sponsored by a Canadian. Before I speak with her, Paul and I sit down with her father, Bouly, the village’s imam, and a few other village elders. We shake all of their hands. Bouly says that his family is, “so happy with sponsorship.” One of the village’s school headmasters, Waly, adds, “World Vision is a special partner.”

That’s important. Sponsorship programs such as this one succeed when the beneficiaries are willing, active participants who become partners. One such partner is Rouguiyatou. In 2015, she was one of the teens in her community who became involved in school governments, municipal councils and child protection associations. In a recent survey in this area, children in the community said they are more involved in decisions that affect their lives today than they were six years ago; the percentage had increased to 81 percent, up from 27 percent. A quote from that same survey said that, “children have become real change actors.”

One way children have brought about positivie change is by becoming a ‘peer educator’ like Rouguiyatou. My translator and I sat down with her on a warm January day in the shade of her family’s small backyard. She has a brother and a sister, and their parents farm rice, maize, cotton and peanuts.

Rouguiyatou had been to school earlier in the day, studying French, history and geography. She’s in the third year of middle school. “I am doing my best to succeed and move on to high school,” she said, adding that she wants to be a midwife after she finishes her education. She has already mastered the basics of hygiene by taking a World Vision course where she learned healthy hygeine practices using a ‘tippy tap’ which is a homemade hand-washing stations using.

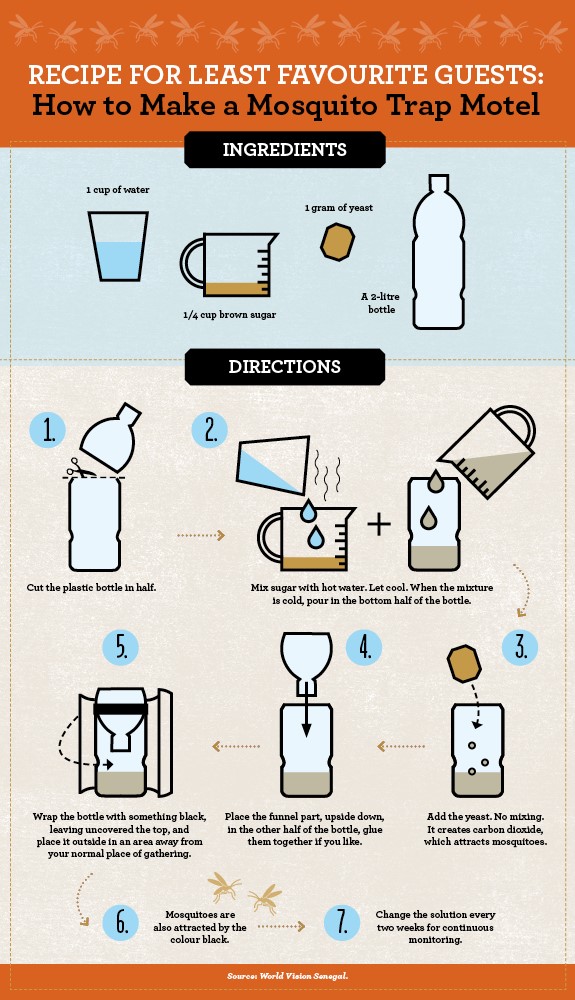

Before taking the health course, Rouguiyatou took a leadership course , which included lessons on how to teach others. With those skills in hand, she started educating others in her village about good hygiene practices, and how to make the hand-washing stations and fly traps. She shows me the book she brings along when she teaches. She credits it and her leadership course as the reasons she is equipped and able to teach her community.

But I wonder, how many adults take cues from 17-year-olds? Well, they certainly listen to Rouguiyatou. Partly because of her character—a friend tells me that Rouguiyatou is a good person to be around—and partly because Rouguiyatou makes it a point to explain why you should wash your hands with soap, as well as boil water you use to cook and get rid of standing water, which only serves as a breeding pool for mosquitoes. And after she explains why, she shows how. She also makes it a point to tell me that because people have made these actions their habits, cases of diarrhea and malaria have gone down.*

*Removing standing water is one reason why the prevalence of malaria in children under five dropped from 13 percent in 2010 to six percent last year.

Rouguiyatou constructs a tippy tap.Because I’m curious, I ask her if she can show me how to make one of the hand-washing stations that are now ubiquitous in her village. Sure she can. We just need an empty bottle, which she finds easily. Next comes the part with the knife and the string. Rouguiyatou uses the knife to puncture a hole in the bottle’s cap and threads a string through it. Then she makes an incision in the side of the bottle and screws the cap back on. Next, it’s the uprights. Rouguiyatou hangs the bottle on a stick that lies across two upright posts. Then the string is back in play. She ties it to another stick that lies on the ground so it acts as a lever. Before the station is ready to use, Rouguiyatou cleans the bottle with a bleach solution and refills it with water.

Rouguiyatou puts the finishing touches on a tippy tap.

Rouguiyatou uses a tippy tap.

At last, it’s demonstration time. Rouguiyatou reaches for the soap and proceeds to wash her hands. She’s quite thorough, like a surgeon or a midwife. When she told me that becoming a midwife was her career goal, I asked her why. Her reason is the same reason she became a peer educator: to help people. She recalled how when her baby sister was born, she liked helping care for her when her parents were away farming. Rouguiyatou is that type of person: selfless and keeps her family and friends and village healthy.

All you want to do is thank her and shake her hand.