Reflecting on gender inequality and the disparity of rights

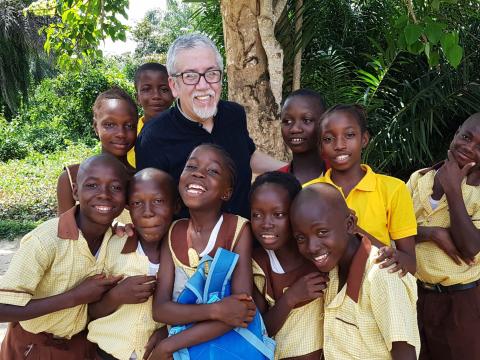

By Patricio Cuevas-Parra, World Vision International

Every November 20th, the international community observes Universal Children’s Day which coincides with the anniversary of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). As a child rights advocate, I strongly believe that this day provides an opportunity to reaffirm the fundamental values of the Convention and celebrate the considerable progress that has been achieved in the development of legislation, policies and strategies to make the UNCRC a reality at national and global levels. This day also invites reflection on the complexity of the pending tasks and obligations of the signatory countries to develop clear national action plans that will ensure a progressive implementation of the UNCRC’s 42 substantive articles.

Based on my conviction that the UNCRC has contributed enormously to new ideological and philosophical conceptualisations of childhood and children’s rights under a policy framework of universality, I would argue that more of our attention should be focused on the right of non-discrimination, which underlies the principle of equality. This focus will enable the galvanisation of notable outlier initiatives into widespread and concrete legislation and practices to guarantee that children’s rights are equal for all girls and boys, regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, ability, religion or any other status. However, a growing body of evidence reveals that children experience multiple grounds of discrimination and their rights are not consistently respected based on their different statuses, a clear breach of the UNCRC’s values.

In this article, I would like to invite you to reflect on children’s gender identities, which have been widely discussed in academia, policy and practice; but, much more debate, analysis and action is needed in order to generate substantial changes within children’s rights approaches. Frequently, gender identities are simplistically addressed in child participation efforts by including the same number of girls and boys across different age groups, but not addressing any social practices or policies that perpetuate gender inequality. Hence, my interest is in understanding how children’s identities, in general, and gender identities, in particular, relate to inequalities and disparities in rights fulfilment between girls and boys and between children and adults and other sub-groups. This interest results from my many years working in, advocating for and researching children’s rights within international development contexts. Over the years, I have witnessed girls across the globe continually facing a wide variety of barriers that prevent them from realising their rights and engaging fully in decisions that affect their lives because of restrictions that can be attributed to traditional patriarchal values and structures.

In some countries, girls are considered to have less value than boys. Girls’ freedom is often limited due to the belief that they need to take care of their honour and are responsible for preventing sexual violence, whilst boys are taught to be independent and self-efficient. Girls are expected to be quiet, polite and delicate, but boys can be energetic, playful and determined. Many girls are banned from participating equally in community activities or discouraged from attending school so they can prepare for marriage instead. In some countries, girls may receive less legal protection from acts of violence than boys. Frequently, girls are allocated fewer educational resources and are expected to carry out domestic chores and care for younger siblings.

Despite the concerns and the calls made to member states by the Committee on the Rights of the Child and the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), gender stereotyping and bias continue to be under-identified and unaddressed, which has a negative impact on the achievement of gender equality. Field experiences illustrate the overemphasis on the traditional roles of females as mothers and wives, which many times are reinforced by books and images in the media that degrade their roles within society. A UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education report points out that both male and female teachers hold low opinions of the intellectual skills of female students, girls have fewer expectations of themselves in and out of school (they believe that their futures consist primarily of being wives and mothers), teachers give girls less feedback, and teachers frequently report that they enjoy teaching boys more than girls. The report also indicates that female teachers’ and girls’ low expectations are reinforced by textbooks, curricula and assessment material, in which no female figures appear, as well as a clear tendency towards the use of sexist language in schools.

Addressing these issues requires theoretical frameworks to explore and understand the relationships between gender identity formation, recognition and rights. Much of the existing childhood literature focuses on agency and competency and less on identities and inequalities. It is also pivotal to reconcile the prominence of the UNCRC as a global framework for universal rights with the relevance of social context, culture, values and social interactions, which are determinant in shaping boys’ and girls’ identities and experiences that form their lives in any given society.

The complexities of girls’ and boys’ lives confirm that there is not a universal conceptualisation of childhood as all human beings bring multiple identities and diverse experiences. Furthermore, I would argue that the simplification and homogenisation of children as a social group undermines the uniqueness of the identities of girls and boys as well as the way they construct and reconstruct the meaning of their lives and interactions with others, which, in many cases, could lead to discriminatory and exclusionary attitudes and practices.

This new anniversary of the UNCRC provides us with a unique platform to discuss the challenges and gaps in empowerment, equal rights and opportunities for boys versus girls. In order to make significant changes, it is crucial to identify the gender-related challenges and avoid gender-blind policies and programmes that exacerbate the differences and do not contribute to the integration and inclusion of all children. While commemorating this day, let us reflect on these issues and think how we can challenge traditional values, beliefs, practices and policies that seriously breach the fundamental human rights of girls and boys.

About the author

Patricio Cuevas-Parra is the Senior Global Policy Adviser for Child Participation and Rights with World Vision International where he leads strategies and programming that ensure that children and young people's participation are central to the advocacy and policy debate. He has a keen interest in looking at cutting-edge child rights advocacy tools and models to enhance children and young people’s engagement in public decision-making.