How the world's most hungry children are paying for the Ukraine conflict

As the Ukraine conflict, climate shocks, and ongoing impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic converge to undermine food supplies and economies, the risk of famine continues to intensify for children and families worldwide. Approximately 50 million girls, boys and their families in 45 countries are on the brink of starvation.

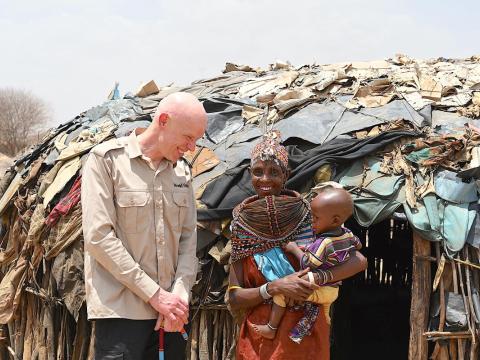

By Andrew Morley, World Vision International President and CEO

For children like 16-year-old Hannah, in a dusty village where the borders of Kenya, Ethiopia and Somalia converge, this devastating drought – and the fatal shockwaves it is sending through this region – are all too real.

It has not rained for three seasons here, and children – who should be safe at home or in school – are walking miles in search of water. This is not just about the immediate pain of thirst and hunger; about mothers checking to make sure their malnourished children are still breathing during the night; or about girls and boys, who should be in school, trekking miles to collect water from snake-infested boreholes.

The drought is tearing into every aspect of life here – ripping apart an already fragile security net for countless children and their families. It follows yet another drought in 2017–2018, a locust invasion in 2019, and is compounded by the lingering socioeconomic and livelihood impacts of COVID-19.

Facing hunger or child marriage . . . or both

On my recent visit to East Africa, I met Hannah, a studious teenager who dreams of becoming a doctor. But the lack of rain means her parents' cattle are dying. In turn, this means they cannot pay her school fees or even provide basic necessities, like food, for their family.

Hannah fears that if she gets pulled out of school, she will be forced to marry in the hope that a husband can better afford to feed her than her parents can. Sadly, World Vision research conducted in 2021 found that this is a self-reinforcing loop – hungry children are 60% more likely to be married than their peers, and married children are 60% more likely to go to bed hungry. While listening to Hannah’s dad speak about the seemingly insurmountable struggles he faces, he challenged me, "What would you do in this situation?" This conversation keeps me awake at night – as parents are forced into devastating situations, through no fault of their own, that no-one should ever have to make. And as a dad of two, I just don't know the answer.

What I do know is that our staff, some who themselves are from the communities they serve and understand these nuances better than I ever can, are doing all they can to fight hunger and bring much-needed hope. Staff like Everlin, who works here in Marsabit and is World Vision Kenya’s ‘child protection safeguarding officer’. She also grew up in a village in northern Kenya. She went hungry often and was herself a recipient of food aid. She was nearly forced into FGM and early marriage – but a missionary intervened. Now, as I saw for myself, she is helping other girls like her stand up for their rights.

Everlin Lenaikoi (World Vision Kenya child protection and adult safeguarding advocacy officer) pictured in Marsabit, northern Kenya

A global hunger crisis . . . people are literally starving to death

It’s estimated that a person dies from hunger every four seconds right now. The UN began tracking food prices almost two decades ago, and in the past months, starvation has skyrocketed to the highest levels ever recorded.

If the hunger crisis was dire before, the war in Ukraine has made it much worse – the number of people living in catastrophic conditions of starvation is four times higher today than just 15 months ago. The conflict's impact on grain, fertiliser, and fuel markets has driven spikes in food, commodities, and transport prices worldwide, forcing ration cuts to refugees and the displaced and hitting the people living in low-income countries reliant on these exports particularly hard. Although there has been a slight dip in food prices since July, they are still at a historic high, and the recent calming doesn't seem to be trickling down to people’s wallets.

Even before the war, hunger had dramatically intensified globally as a result of COVID-19 lockdowns, entrenched conflict in many countries, and the impacts of climate change. In 2021, there were 1.5 times more people at risk of famine than in 2019 pre-pandemic.

In drought-parched northern Kenya, I witnessed livestock carcasses littering the landscape and desperate pastoralist families share the tiny amounts of food that remain between their children and their last few animals. Many organisations providing food aid are faced with impossible choices, having no alternative but to reduce the quantity, quality, and frequency of food assistance because there is simply not enough to go around. Even though humanitarian funding is at a record high, the needs continue to outpace the support, and I am terrified that we won’t be able to feed millions of hungry children and their families if this funding gap is not closed.

The challenge is large, but we know we can avert this crisis if we act now. We just need the will to do so. After all, the Ukraine Response has been a model of solidarity with 66% of the total requirements funded already. It will be a moral failure if we do not make the same commitment to feed millions of the world's most vulnerable people, and prevent girls like Hannah from being pushed out of school and into child marriage.