The Silent Pandemic

Yesterday conflict ravaged their countries.

Today COVID-19 threatens their lives.

Now a silent mental health pandemic menaces their futures.

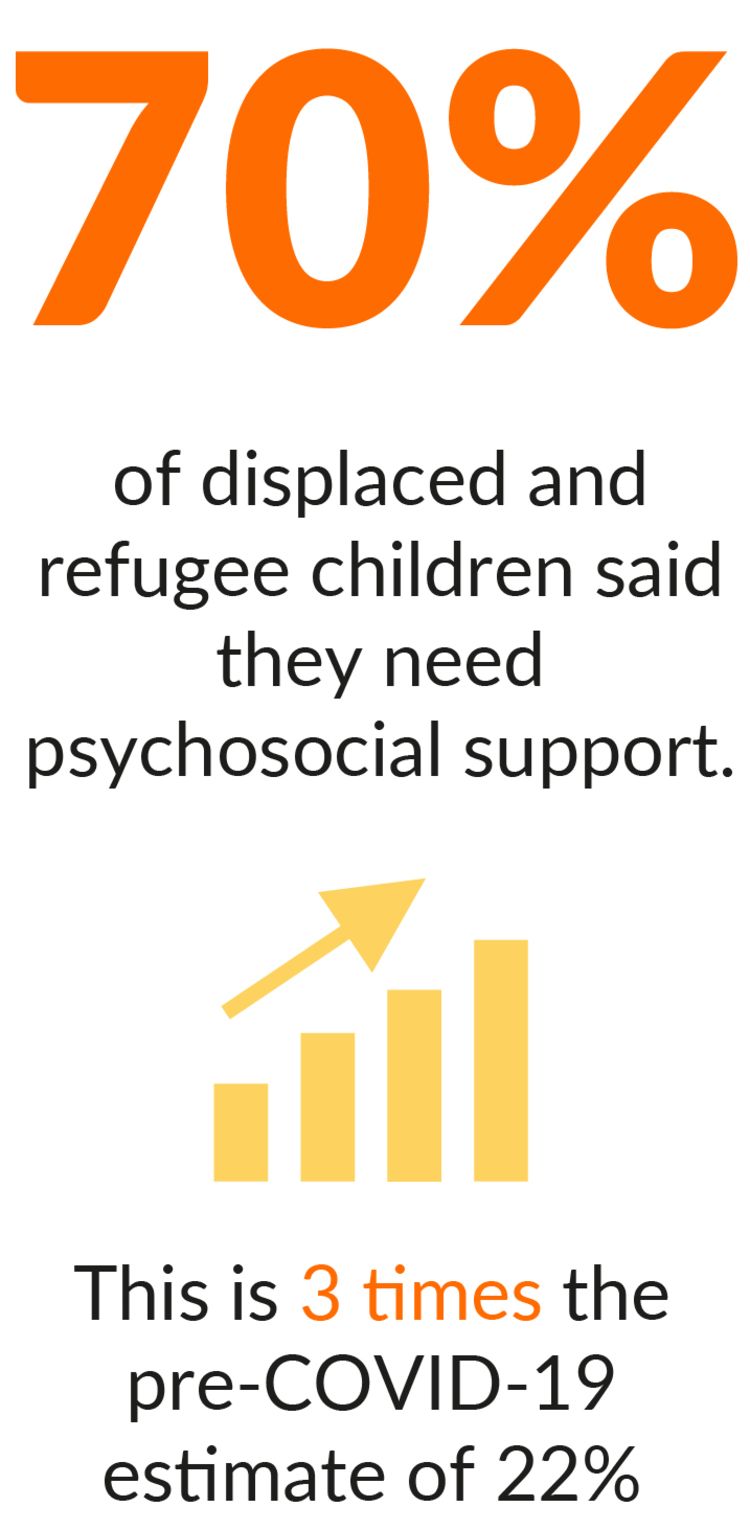

Displaced and refugee children are three times more likely to ask for mental health support due to the effects of COVID-19.

Children, particularly those affected by conflict, are the hidden victims of the COVID-19 pandemic.

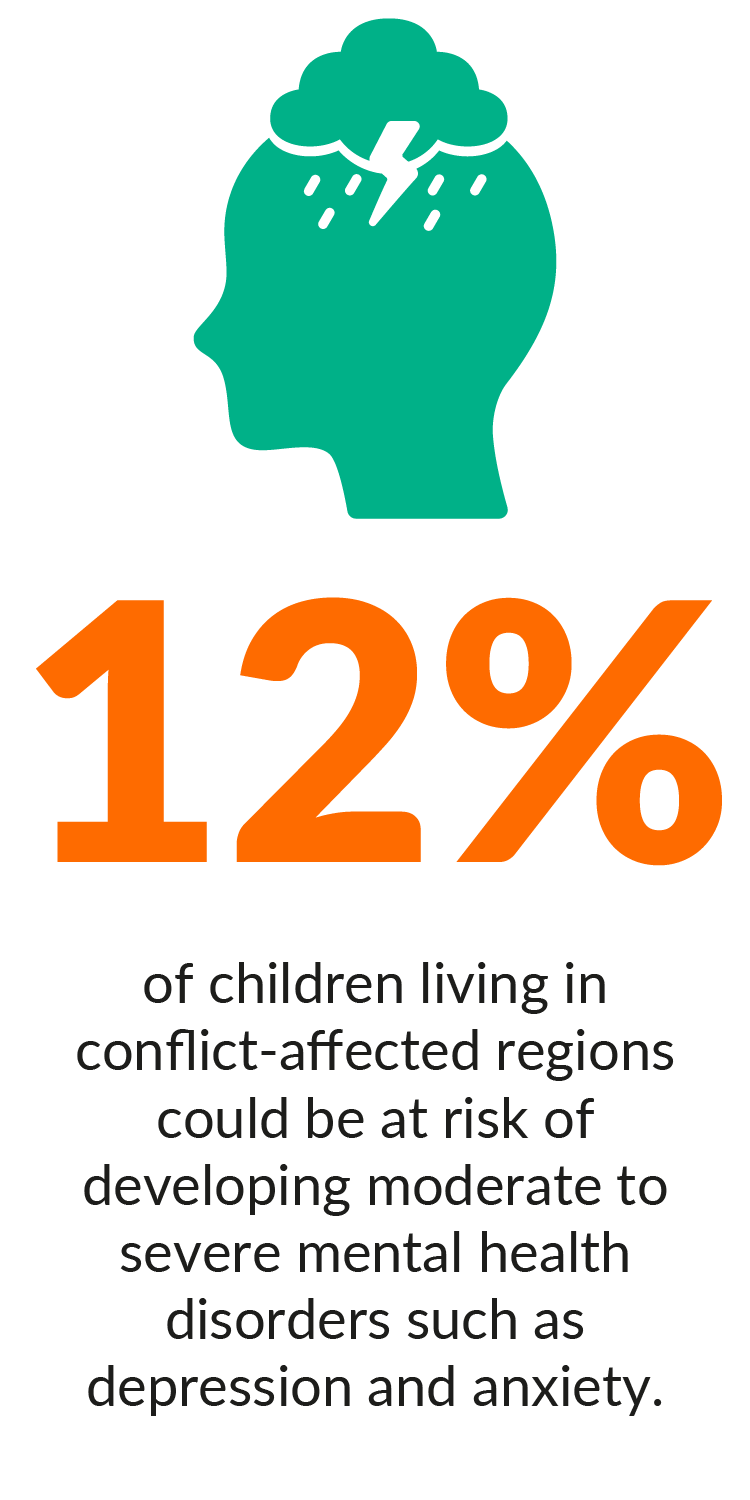

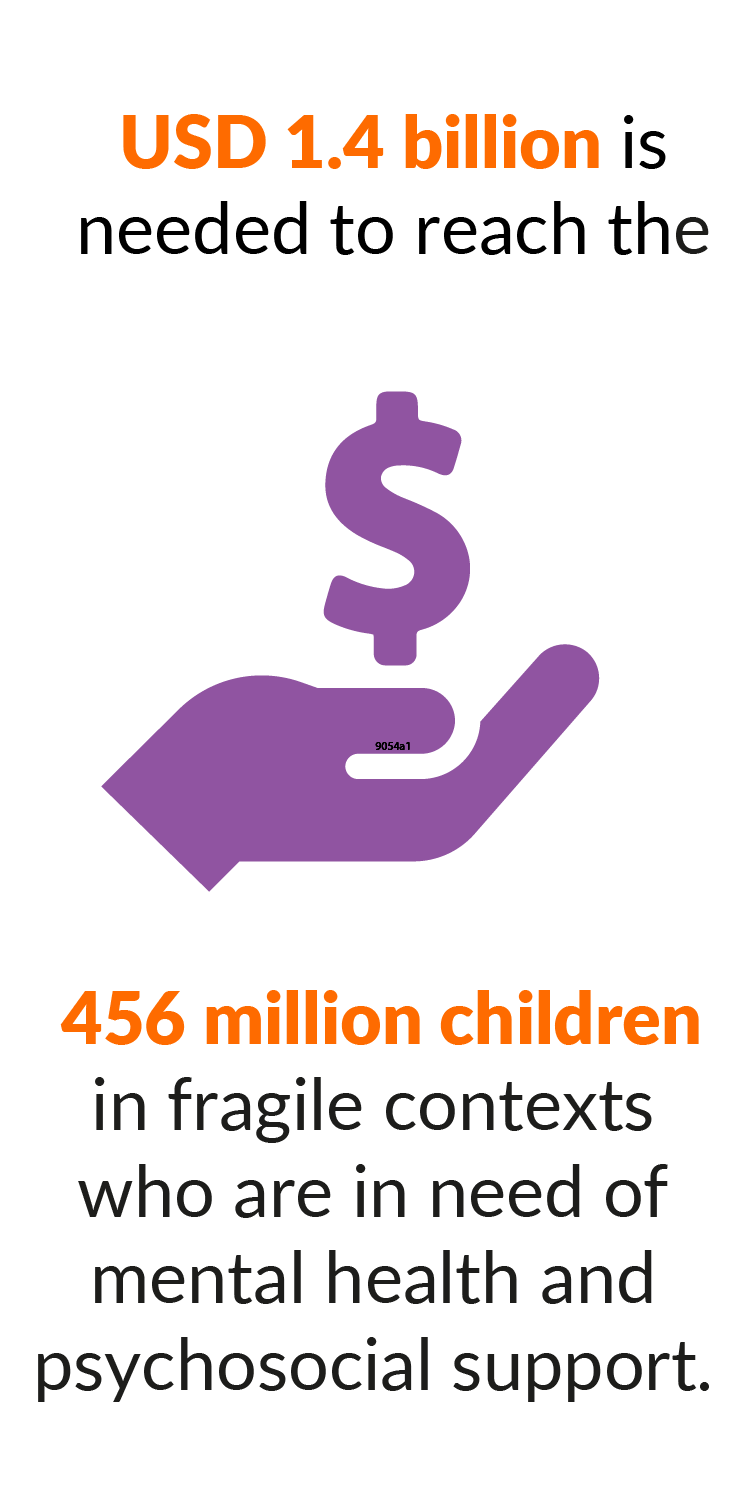

800 million children and young people live in fragile and conflict-affected areas. Of those, 456 million are at grave risk of mental health issues.

Although the world is currently focused on combating this global health crisis, its long-term impact on the mental health of children living in conflict-affected countries is not fully understood nor on the minds of political decision-makers.

Unless we act to address this now, the devastating disruption caused by COVID-19 will have lifelong and potentially life-threatening consequences for a generation of the world’s most vulnerable children.

DAILY CHALLENGES

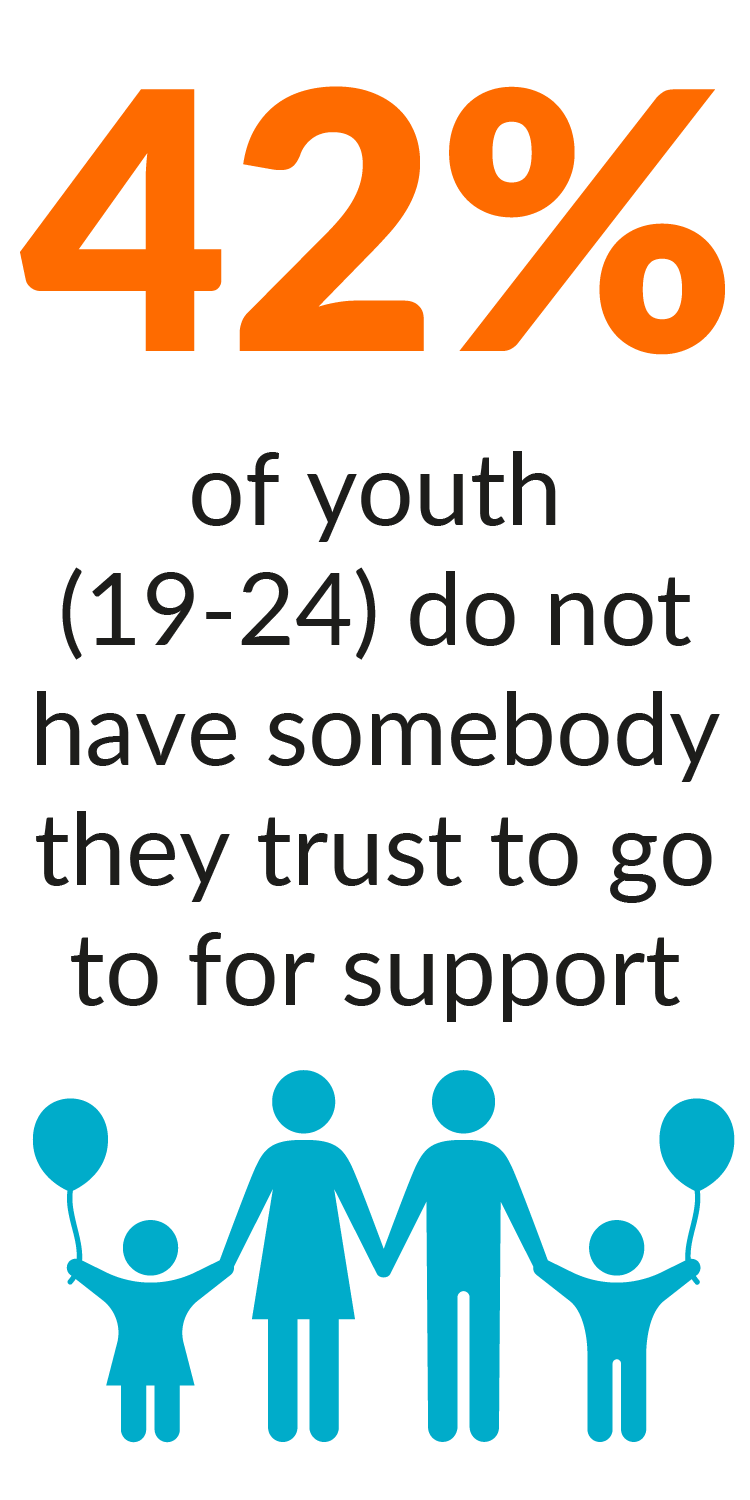

A child or young person growing up in a conflict zone already has more than enough to deal with: the loss of the family home, often the death of one or several family members, the challenge of settling in an unfamiliar and often unstable environment, the interruption of school, and the dispersion of childhood friends.

Many of these children have shown remarkable resilience but the global COVID-19 pandemic has compounded their pre-existing stresses.

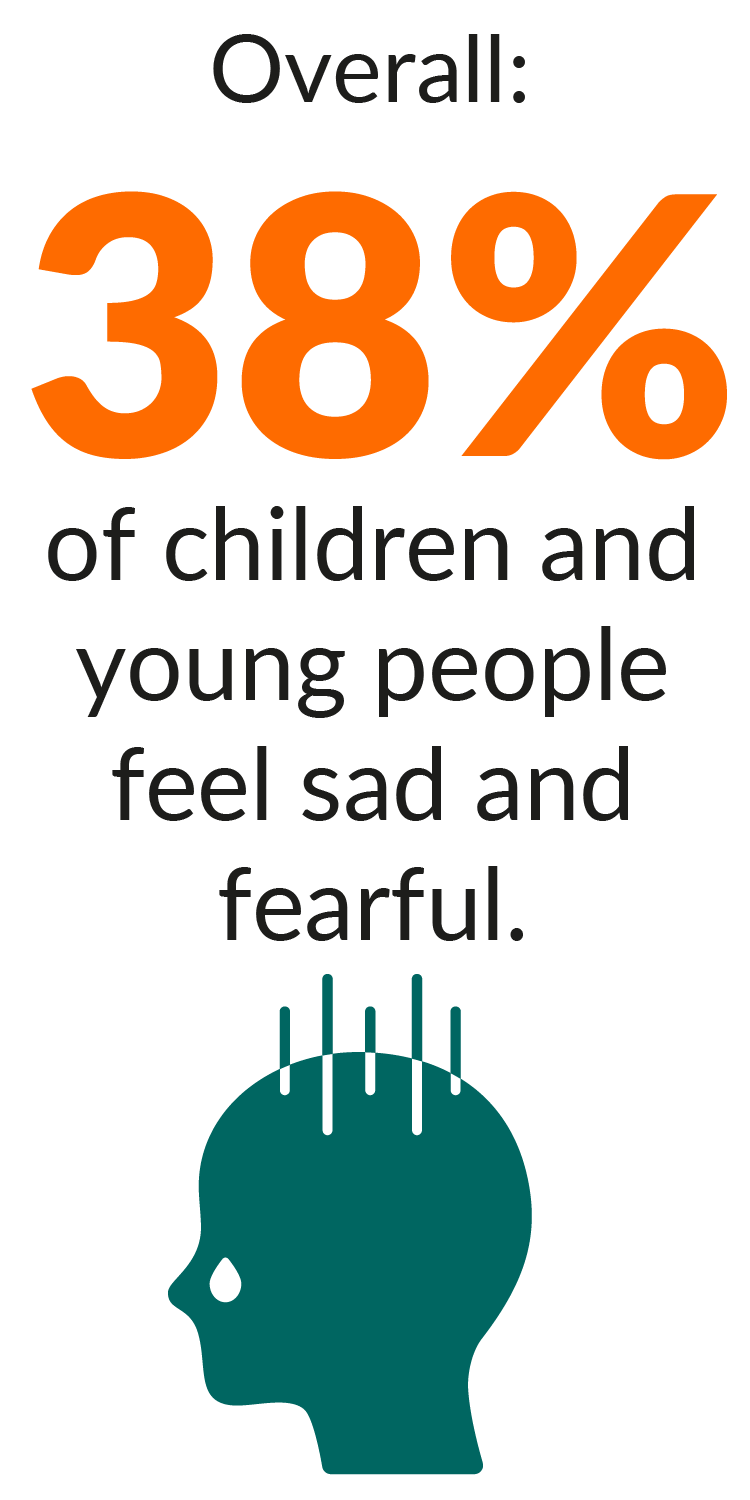

Most children and parents we spoke to were worried about contracting COVID-19 themselves or feared that their relatives may die from the virus. 40% of children and 48% of parents indicated that COVID-19 is the main factor affecting their emotions.

Worries included contracting COVID-19, fear for their family members, and anxieties about school closures, limited access to basic services like water or health centres, and a struggle to make ends meet due to the economic effects of lockdowns and other COVID-19 containment measures.

In addition, armed conflict, compounded by the impacts of the pandemic, is currently threatening to push 270 million people worldwide to the brink of starvation, doubling from 135 million before the pandemic.

Across all six countries, children’s mental health and well-being is deteriorating significantly. Without support, a generation of children risks being permanently affected by the mental health fallout of the pandemic.

How much is too much?

“Being safe is a challenge. I am constantly scared. Scared of people and what happens in my country. Now poverty also scares me.”

Amina, 16-year-old girl

No child should have to carry the psychological scars of war and pandemics.

Children who have previously experienced traumatic events are more vulnerable to new stressors. The stress of the pandemic may resemble past traumatic experiences such as bombing, escape, or conflict. Fear of death, destruction, injury, and loss of loved ones may resurface. Some children may not be stressed by COVID-19 itself, but by what it brings up in them.

Based on our analysis, an estimated 456 million of these children are in need of support.

But less than 1% of all humanitarian health funding is estimated to go toward meeting these needs.

Children in conflict-affected areas already had limited access to mental health and psychosocial support services even before the pandemic.

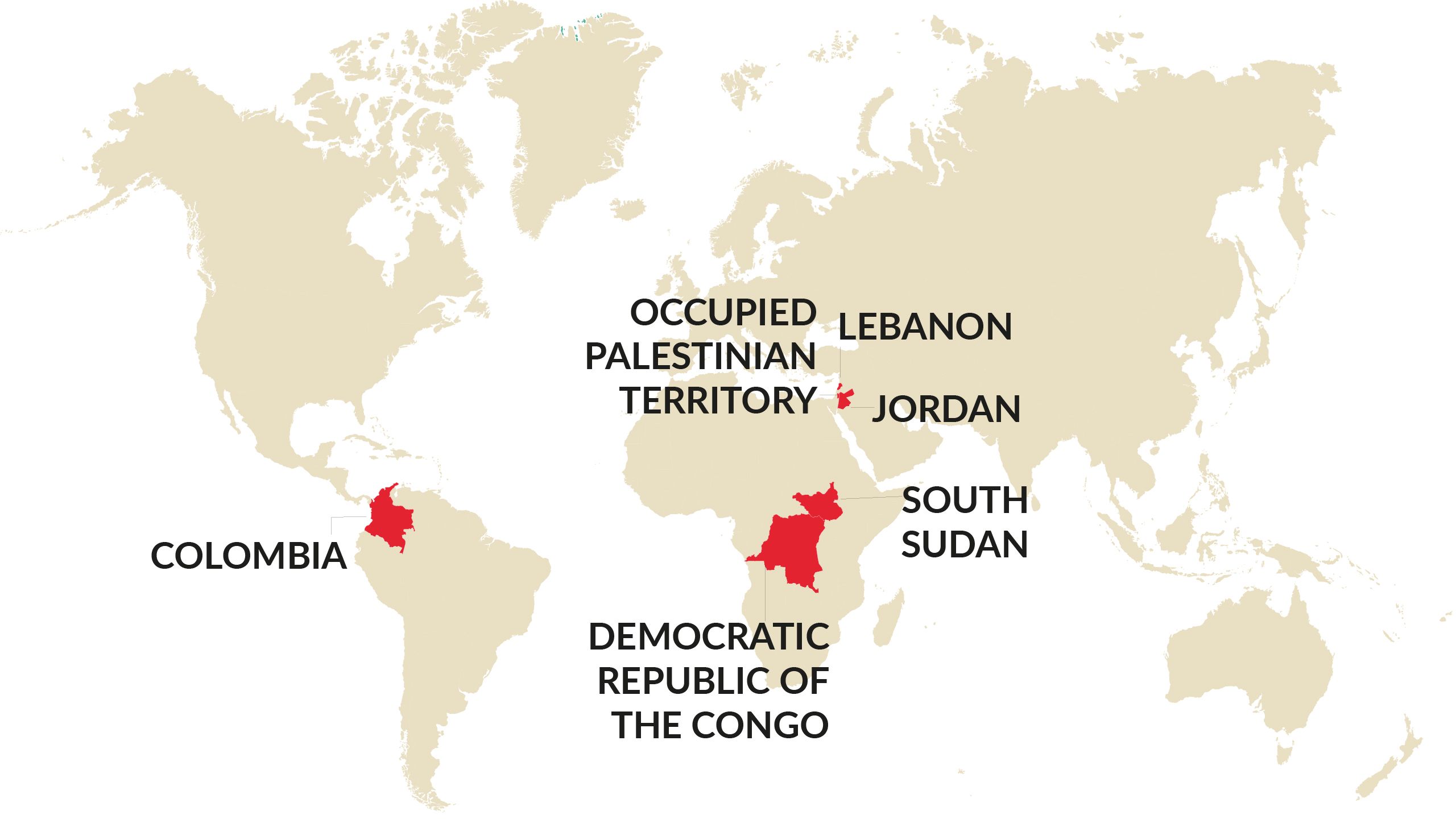

WHERE WE SPOKE TO CHILDREN

COLOMBIA

Even though a peace agreement was signed, conflict-related violence and serious abuses of human rights continue. The level of domestic abuse and gender-based violence has also increased as COVID-19 has affected the mobility of children in urban areas.

In rural areas, children are not in quarantine, and they are at increased risk of being “seduced” or forcibly recruited into armed forces or gangs as they can no longer attend schools. Remote learning is not inclusive of rural areas due to poor internet connection.

Many families are hungry. With poverty levels increasing, the nationwide lockdown measures reduce the ability of people to take the necessary precautions, leading to higher risks of infections. An increase in symptoms of anxiety is reported as a direct result of the pandemic.

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF CONGO (DRC)

The DRC has known nearly 20 years of instability and conflict. More than 3 million children are displaced, half of them in the last 12 months. Children have witnessed friends and family members hacked to death. Particularly in the eastern zone of the country, community health centres and schools have been looted, homes burned, and whole villages destroyed, forcing children and families to flee to survive.

The DRC has one of the world’s poorest health systems, a situation that has been exacerbated by the country’s battle with Ebola, cholera and now COVID-19. Today, more than 27.3 million people across the DRC are facing high levels of food insecurity (crisis and emergency), including nearly four million children under the age of five. Before the pandemic, children were at risk of exploitative labour, exploitation, sexual violence and forced marriage.

All of these risks are now being compounded by the double pandemic of COVID-19, and in Eastern DRC, Ebola.

JORDAN

Jordan currently hosts over 2 million refugees, representing over 20% of its population. To contain COVID-19, the government has closed schools, instead providing TV and internet-based education. But access is hard for refugees and poorer and marginalised Jordanians. In the camps, the internet connection is bad, there are not enough devices, and teachers are often unmotivated. Many vulnerable parents do not have the ability to teach their children due to their own illiteracy. The lack of access to education represents one of the key stressors for children and young people. Refugee children are also often excluded from access to national physical and mental healthcare resources.

“Online education is not working here inside the camp. The internet connection is bad, the teachers do not care about us and we do not have electronic devices."

LEBANON

Multiple crises, including a massive explosion in Beirut’s port, an economic collapse, rising political instability, and the COVID-19 global pandemic have created severe social and economic hardships for the population, including 1.5m Syrian refugees. A regional conflict is looming. For this reason, COVID-19 awareness and access to information and care is pushed to the background.

In addition, the number of street children is increasing. They are at risk of kidnapping or recruitment into militant or radical organizations, and suffer from a gap in their education. Success rates for online education are low because many lack access to the internet and there are frequent power cuts.

OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY (oPt)

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the already dire health, socio-economic, and protection situation in the oPt. An estimated 2.45 million Palestinians will be in need of humanitarian assistance in 2021. Amongst the most vulnerable are children in detention, who are isolated and therefore not allowed to see their parents or lawyer.

Domestic abuse and sexual and gender-based violence against women and children has increased, exacerbated by COVID-19 restrictions and the resulting economic deterioration. The loss of parents' incomes during the pandemic has made it difficult for them to provide for their children. Mental health service providers also reported a spike in calls to hotlines and for phone counselling from people threatening self-harm and general psychosocial distress.

SOUTH SUDAN

Recently ravaged by floods and locusts, COVID-19 has further impacted South Sudan, causing a drastic decline in domestic production and a sharp increase in living costs. The result has been worsening food security and living conditions for millions of children.

South Sudan is struggling with chronic shortages of hospital beds, COVID-19 testing equipment, water, and oxygen. Children are at increased risk from rising inter-communal conflict and famine, and a chronically under-developed health system often unable to meet the most basic primary health needs for child survival. Recent assessments found that 30 per cent of children had behavioral change, showing signs of distress due to repeated exposure to conflict and shocks. Tens of thousands of children and youth are left without access to education. Remote and homeschooling are simply unavailable. Lockdown measures have increased idleness among youth and children, restricted the movement of girls and women who are at an even greater risk of gender-based violence, and increased the risk of recruitment of girls and boys into armed groups.

“When there is peace in the family and in the community, I feel happy and safe”.

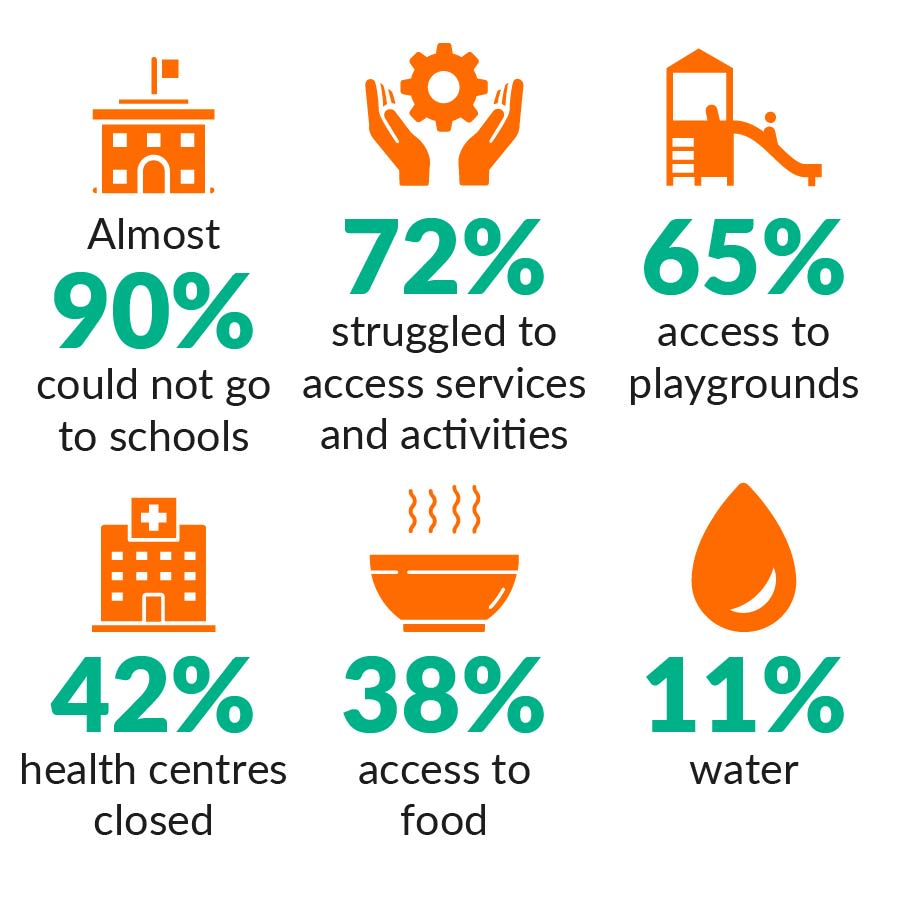

Children and young people were affected as services became less available due to the pandemic:

The under-prioritisation and underfunding of mental health in humanitarian responses is a key barrier to supporting children affected by conflict.

We are witnessing a silent pandemic of mental health disorders and stressors among children and young people in the wake of conflict and the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, we have some of the solutions ready at hand to address this crisis. There are proven ways to support children’s mental health in humanitarian settings, from expressive art, music and play, and child-friendly spaces, to clinical treatments that can be rolled out at scale.

What is needed is global leadership to scale up these initiatives and ensure that mental health services are made a critical part of all humanitarian responses.

No child should have to bear the psychological scars caused by wars or pandemics.

During this study, children clearly told us what they want:

They want stability and dignified living spaces.

They want their families to be able to work and to have jobs to support themselves.

Children want access to reliable information and quality education so they can control their futures.

And overwhelmingly, they asked for psychosocial support to help them as they rebuild their lives.

When given an opportunity, children and young people act and advocate social change. When empowered, children are not helpless victims – in fact, they often become powerful catalysts who can bring social change in a crisis. They are true heroes and have the ability to improve their own circumstances.