5 tips: Promoting women’s economic empowerment and engaging men

Livelihood expert Ellie Wong outlines out what World Vision has learned about how empowering women to balance both income generation and care work

Over the last 7 years with World Vision, when I’ve visited different communities, one thing has remained consistent: women and men producers – mothers and fathers – all want to see a better future for their children and families. Mothers want to create a better future for their daughters.

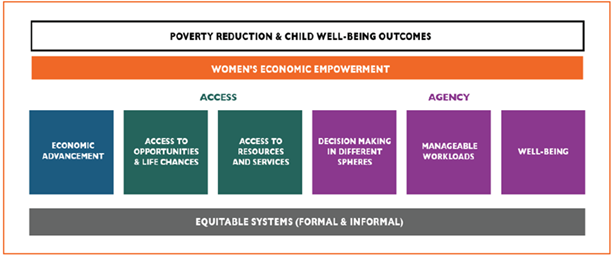

As a child-focused organisation, World Vision’s new Women’s Economic Empowerment framework and Programme Quality Assurance Standards (PQAS) aims to build a common understanding of the pathways of change required for women to be economically empowered alongside men – to the benefit of their children. Here are five tips for implementing the framework in field programmes:

1. Make holistic women’s economic empowerment outcomes the end goal

World Vision’s new framework promotes a holistic definition of women’s economic empowerment. We have four key domains: economic advancement, access, agency and equitable systems where women can thrive.

What does this look like in practice? It means that women have improved income generation opportunities and access to opportunities for skills development, knowledge, resources and services. It also means that women have agency and are able to influence decision making in their households and places of work. Women are able to balance paid and unpaid care work, and their well-being is protected. Finally, it means that there are equitable systems where women can thrive alongside men. This means that formal systems, like laws and policies, and informal systems, like social norms, are supportive of women’s roles as economic actors, including balancing paid and unpaid care work.

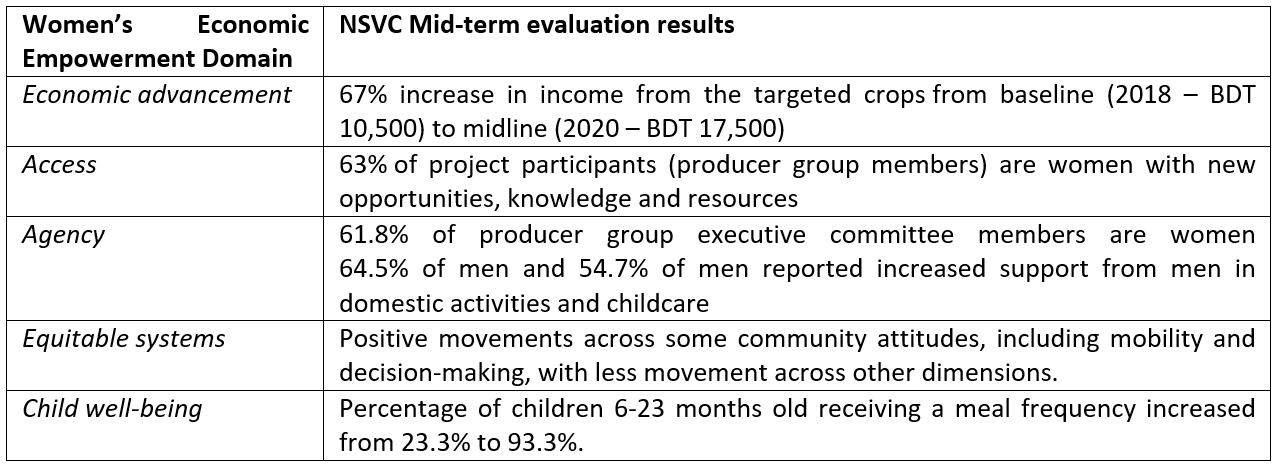

2. Prioritise measurement of multiple women’s economic empowerment domains

Livelihoods programmes often prioritise the measurement of economic advancement and access to opportunities and life chances, resources and services. However, it is critical to also measure changes to women’s agency and equitable systems – including how programmes are addressing social and gender norms. This helps us shift the dial on what we mean by success in programmes.

For example, how can women, children and their families benefit from their increased incomes and better jobs with decision making over how that income is spent? Therefore, we need to measure changes in decision making, including household expenditure like children’s education and nutrition. We also need to measure the impact that programmes are having on women’s manageable workloads, as women take up new economic activities. One of the more time and cost effective ways that we can do this is measuring time spent on leisure and rest by women and men.

3. Work with market actors, communities and households as agents of change

In order to sustainably empower women to participate and benefit from economic markets, and to promote more inclusive markets, programmes can adopt a two-prolonged approach. First, we can work with – and through – market actors on gender-inclusive business models and practices that engage women and men living in poverty as producers, consumers and employees. Second, we can directly engage women, men and communities to address gender-based constraints.

For example, in the Nutrition Sensitive Value Chains (NSVC) project in northern Bangladesh, World Vision is working with agri-businesses to engage women producers like Monjuri as consumers of quality seeds, while also engaging households and communities on gender transformative programming that seeks to challenge harmful social norms and unequal relations and replace them with equitable alternatives.

World Vision has worked with Promundo to adapt their MenCare approach, which seeks to promote gender equitable relations with couples. By engaging partners of women project participants like Monjuri’s husband Mohammad, we can better influence things like household decision making and sharing the care work. This has been complemented by community level social norm change, through utilising folk songs, engagement with faith leaders and community dialogues.

In addition to selecting value chains that have low entry barriers for women, such as those that can be done close to the home, engaging men in the care work is key in ensuring women’s manageable workloads in a context with a limited formal care economy.

Mid-way through the project, there has been strong progress across multiple empowerment domains.

4. Be intentional and practical in promoting women’s agency

Agency – or the ability to make and act on economic decisions - can often seem abstract. However, programmes can intentionally promote targeted dimensions of agency. For example, financial literacy is a key entry point given a household budget is all about decisions linked to financial priorities and savings goals. Improving women’s financial decision-making links closely with child well-being, as we know women are more likely to invest in children’s education and nutrition.

World Vision’s new pilot Gender inclusive financial literacy training (GIFT) package, not only promotes access to financial management skills but also promotes women’s voices in financial decision-making alongside men. To promote sustainability, World Vision Indonesia, as part of the ANCP MORINGA project, is working in partnership with Credit Unions (CU) to implement GIFT alongside the loans that they offer.

“Even though I was a little hesitant at first, GIFT provides a new perspective on gender in the context of building family financial literacy, especially in the context of patriarchal culture. By incorporating GIFT into CU training, this enhances CU's branding and we are even contracted by other organizations to train GIFT to their assisted communities. This has an impact on increasing the number of CU members.” – Korenlis Mail, Manager of Credit Union in East Nusa Tenggara, Indonesia.

5. Listen to women and prioritise adaptive management

Effective programmes need to prioritise understanding women’s perspectives and voices, alongside men, from the beginning. This can inform how we understanding key challenges linked to women’s economic empowerment domains and the corresponding strategies and interventions to realise holistic outcomes.

Given the complexities in each context, learning and adaptation of approaches is key. For example, when starting the MenCare intervention in Bangladesh in the NSVC Project, certain tasks were socially acceptable — like having men take the children to the doctor and helping their wife with food prep — but other care work traditionally conducted by women — like leading the cooking — was perceived as too much of a change to social norms. Mothers-in-law were a big obstacle to engagement of men in the care work.

In response, the project implemented a staged approach, starting with quick wins, and working towards more difficult norms over time. The MenCare activities were designed to not only include couples but also the mothers-in-law as well. The project is now also providing MenCare training to religious leaders so that they are allies in gender equality and women’s economic empowerment.

Word Vision’s global footprint in livelihoods programs spans over 65 countries. With a new intentional approach to gender equality, we can economically empower both women and men – mothers and fathers – to better provide for their children.

For more information, download our WEE Framework and Program Quality Assurance (PQAS) Briefing Paper, which summarises the approach, indicators, and evidence. You can also download:

- WEE Framework and PQAS Technical Guidance. An Implementation Note summary is also available on 10 standards for design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

- WEE Indicator Guidance and Tools

- Gender inclusive financial literacy training (GIFT) manual and technical note.

- Impact Brief: Nutrition Sensitive Value Chains for Smallholder Farmers Bangladesh Project

You can also read more about the World Vision’s approach and programmes in first and second instalments of Marketlinks’ Market Corner for March 2022, which focused on the care economy.

Ellie Wong is World Vision Australia’s Economic Empowerment Manager and one of the lead authors of WVA’s Women’s Economic Empowerment technical resource materials.