This Christmas, for Southern Africans the issue of aid is live

Tigana Chileshe writes that as people across Southern Africa approach Christmas, their immediate focus is finding food, after failed crops and drought

19 December, 2024

Forty years ago, famous musicians and singers came together to record "Do They Know It's Christmas?" to raise money for the famine in Ethiopia. While the lyrics “Do they [Africans] know it’s Christmas time at all?” are now rightly criticised as patronising, the situation in Southern Africa today is a stark reminder that hunger, and hardship persist.

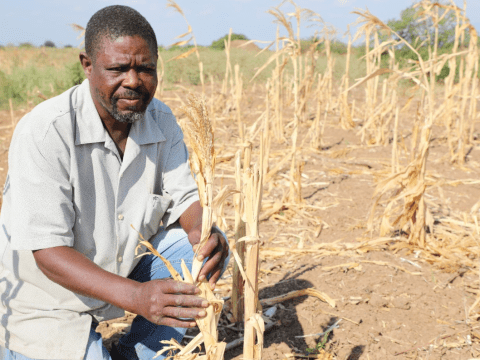

As 2024 draws to a close, an El Niño-induced drought described as the worst in 100 years combined with the lingering impacts of COVID-19, has left millions in Southern Africa with little to celebrate this Christmas. Instead of worrying about Yuletide gifts or festive feasts, many are desperately concerned about where their next meal will come from, whether the rains will finally fall, or if they will be forced to sell their remaining livestock just to survive.

Statistics in Southern Africa show that malnutrition and hunger among children have sharply increased, pushing vulnerable communities further into despair. This drought, driven by an El Niño phenomenon that’s been made worse by climate change, deforestation, and economic struggles has reversed hard-won progress.

It’s hard to put into words what it feels like to witness this devastation first hand, but the numbers paint part of the story. As of November 2024, 61.7 million people across Southern Africa about 17% of the region’s population needed aid. According to the World Food Programme (WFP) about 21 million children in southern Africa were estimated to be malnourished due to food insecurity after crops failed as of October 2024.

At the onset of the crisis, the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) region launched a $5.5 billion regional humanitarian appeal in May to address the impacts of drought, floods, and long-term climate resilience, unfortunately donations remain far below what’s needed. In November 2024, an addendum was made to the appeal that increased the appeal budget to $6.5 billion with an increase in the number of people in need of assistance from 61.7 million to 79.8 million

In countries like Zambia, Malawi, Zimbabwe grappling with the drought’s toll, the human side of this crisis is evident daily. Families are making heart-breaking decisions: In countries like Zambia, Malawi, Zimbabwe grappling with the drought’s toll, the human side of this crisis is evident daily. Families are making heart-breaking decisions: marrying off daughters to reduce the economic burden, pulling children out of school, and selling off critical livelihood assets such as cattle and goats—or worse, ancestral land.

Water scarcity is compounding the crisis, leading to severe load-shedding that crippling economies in Zambia and Zimbabwe which share a hydroelectric power station powered by the Kariba Dam. The dam is experiencing record-low water levels, severely impacting its operations. In other areas, water sources for people and animals have dried up, fueling resource-based conflicts.

“I rely on my children to help me with food, but they’re also struggling," shares 66-year-old Lessy from Zambia. “Now, because everyone is hungry, thieves have stolen my chickens. My maize barn is empty, and so is my chicken coop.”

Sozinha, a 16-year-old from central Mozambique, shares a similar story of despair: “Because of hunger, other children and I dropped out of school.”

As someone working in humanitarian emergency communication, based in Southern Africa, in Zambia, a country that has gone through this drought, I see the human side of this crisis every day. Working alongside World Vision Southern Africa regional team’, I have been part of a multi-country response supporting Angola, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Since the World Vision declaration of the El Niño multi-country response in May, we have engaged in numerous initiatives to raise the drought’s profile and advocate for critical funding.

One such effort involved partnering with the World Food Programme Southern Africa in October for a communications and advocacy campaign as part of World Food Day Commemoration. Together, we profiled stories of those affected, like Sozinha in Mozambique and Nyaradzai Muradzi in Zimbabwe, a 52-year-old woman who lost all but one goat to drought and theft. “Our land is dry, and we have no access to water. Thieves stole all my goats, and I can barely feed my family,” Nyaradzai laments.

Through 34 social media channels between World Vision and World Food Programme (WFP) across Southern Africa, we amplified the voices of those impacted and profiled our partnered interventions in communities alongside governments. These stories have been heartbreaking to share, but they’re also a call to action. Despite these efforts, the challenges remain immense. SADC member states have mobilised resources from bilateral and multilateral partners, but the response is still insufficient as the amount mobilised so far is below the amounts needed according to the Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Secretariat.

With the 2024/2025 farming season now underway, the outlook remains poor. With delayed or largely no rains save for a few drops in November followed by heat waves in December across most parts of Southern Africa like Zambia, Zimbabwe and Malawi, this has left many farmers who planted seeds holding on to hope that the rains would continue gripped by anxiety and uncertainty.

Last year’s drought was a brutal reminder of how climate change hits the most vulnerable the hardest. A point that was well articulated at COP29 in November when world leaders met in Baku, Azerbaijan and agreed to a new climate finance goal: $300 billion annually by 2035 to address several critical aspects of the global response to climate change such as adaption measures, mitigation measures, loss and damage, capacity building and technology transfer.

But this amount is far short of the $1.3 trillion developing countries were pushing for and nowhere near enough to meet the Paris Agreement goals. If this amount is not increased at the next COP30 in Brazil, the people least responsible for global emissions like low income and developing nations in Southern Africa are the ones who will continue to suffer the most from the fall out of climate change.

It’s December, and we are only a few days away from Christmas, a season of cheer, generosity, and hope. But as the world celebrates, millions across Southern Africa, who rely on rainfed agriculture, are bracing for yet another year of hunger and hardship. Forty years ago, in 1984, Live Aid called the world to action against famine in Africa. Today, we need more than a song. We need leaders and communities to step up with action, courage, and resources.

Here are three things that must happen:

Policy Change – Governments must implement climate resilience policies to mitigate drought and adapt to shifting weather patterns.

Emergency Relief – Increased funding for immediate food aid, water access, and support for families in crisis.

Greater Investment – Scaling up climate financing for sustainable agriculture, regreening efforts, and water conservation technologies.

So, as we celebrate this festive season, let us act with compassion and urgency. Let’s pray for rain—but also demand bold solutions. The families across southern Africa cannot wait for another “worst drought in 100 years.” May the spirit of Christmas inspire us all to make a difference.

Learn more about our response here

By Tigana Chileshe, World Vision Southern Africa Communications and Public Engagement Lead.