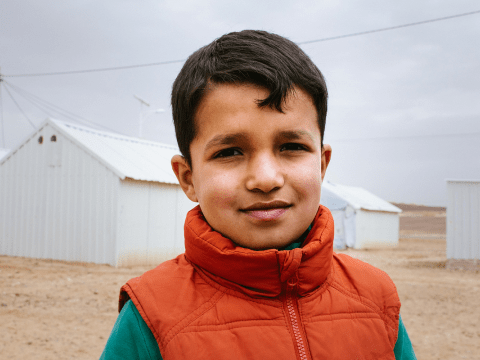

Earthquake-affected unaccompanied and separated Syrian children shouldn’t fend for themselves.

Balquees Bsharat, highlights new research by World Vision that has uncovered heart-breaking realities for children displaced by war and natural disasters.

19 August, 2024

I know how bad life has been for Syria’s refugee children—I started my work in Syria with UNHCR back in in 2013. However, it wasn’t until our research on the impact of the February 2023 earthquakes on unaccompanied and separated children (UASC) in Northwest Syria and Southern Türkiye, that I understood just how bad things had become for them.

The earthquakes that struck North-West Syria and Southern Türkiye on the 6th of February 2023 killed over 56,000 people and affected a staggering 26 million people including at least 7 million children, in some way. These disasters decimated critical infrastructure and destroyed building and houses, leaving millions homeless and without access to lifesaving services.

Given the protracted nature of the Syrian crisis I anticipated a significant number of unaccompanied and separated children (UASC) as a direct result of the conflict and the earthquakes. However, there was little data to back up how many children were affected and to in what ways, and so I was pleased when our organisation determined to do research into this issue.

Insights from the data

Our research observed a dramatic increase in the number of unaccompanied and separated children, and over half of the community members we interviewed reported knowing of numerous UASC in their areas who lost parental care because of the earthquakes. Additional factors, such as the ongoing conflict leading to homelessness, socio-economic hardships, as well as cultural issues like divorce and remarriage of caregivers, further contributed to the rise in family separations.

This is bad because unaccompanied and separated children are increasingly vulnerable to child labour, child marriage, and severe mental health challenges. The earthquakes exacerbated these vulnerabilities, particularly for girls, due to societal and gender norms. A significant majority of community members told us about a rise in child marriage, child labour, exploitation, and mental health issues among UASC following the earthquakes. Many caregivers identified mental health as the area with the highest level of need among these children.

One of the most alarming aspects of our research findings was the lack of detailed data on UASC, particularly concerning their gender, disability, and refugee status. This lack of data renders these children largely invisible, both as a group and in their individual diversity.

Lacking support

We also found that the chronically inadequate support for UASC has led to a significant increase in unregulated residential care, unsupervised living situations, and child-headed households, further exposing these children to heightened protection risks.

Another finding that struck me is that, despite the critical role of family-based care (particularly kinship care in both regions) this care model receives minimal recognition and support. Kinship caregivers, who often receive no state assistance and humanitarian responses frequently fall short in providing essential support, affecting the sustainability and effectiveness of this care model. These adults are also struggling with the mental and emotional impacts of living through conflict and earthquakes.

Recommendations

The research report contains a variety of recommendations, but I’d like to take this chance to give the children themselves a chance to be heard. In Northwest Syria and in Southern Türkiye, they told us that they needed:

- Inclusive and safe places to play and learn

- Kind and supportive family and community involvement in their lives

- Essentials like food, clothing and shelter

- The chance, and financial support, to go to school

- Psychological and emotional support to help with trauma and loss

I hope that adults everywhere do what they can to provide what are, after all, the things that every child should expect and receive.

This crisis has no immediate solution, and as it drags on, it is the children who suffer the most, particularly UASC, who are among the most vulnerable. The heart-breaking stories we heard stress the urgent need for action to protect and support these children, ensuring that they are never forgotten or left behind.

Learn more about World Vision’s Syria Crisis Response here

Balquees Bsharat has been World Vision’s Advocacy Advisor since 2013. She holds a master's degree in Human Rights and Human Development, as well as a bachelor's degree in Accounting and Commercial Law. She has 6 years of experience with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), where she undertook various roles, particularly in the Field and External Relations departments. Later, she moved to the Geneva Office of the Special Envoy for the Central Mediterranean Situation, working as a researcher and media officer. Following that, she joined the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime as a researcher and analyst, where she analysed trends and patterns that could indicate potential spikes in organized crime affecting community resilience and human rights.