Approaching The Environment With A Changed Mindset For Sustainable Living

Under the shade of a tree sits Isaac Chelal whose English eloquence is unmistakable as he vividly narrates the story of how the Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration (FMNR) approach began when Tony Rinaudo found a regenerating stump in a deserted area with no vegetation in Niger. The 66-year-old farmer does not miss out a detail.

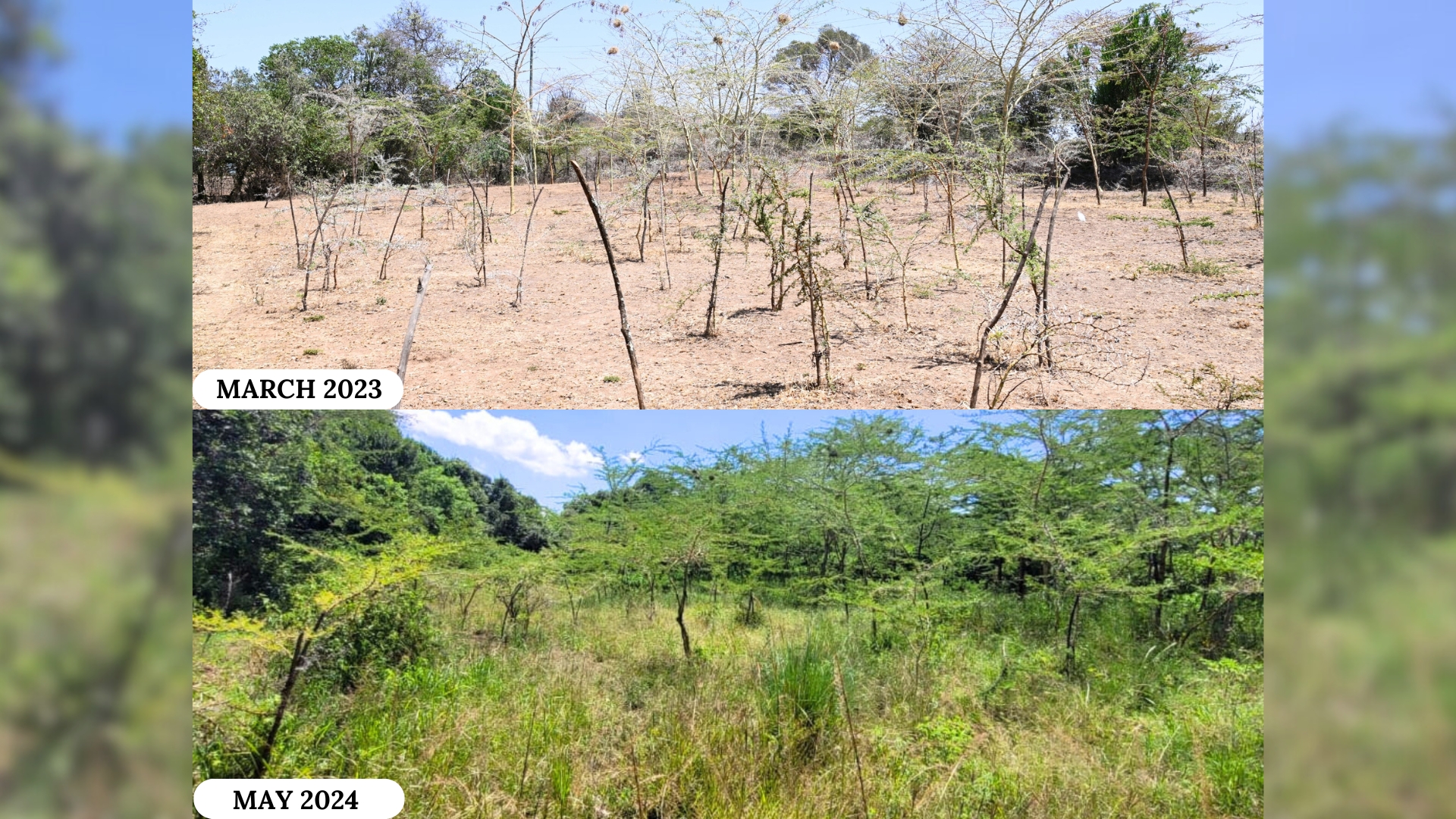

Isaac and his wife Lina Cheruto hail from Metkei Village in Nakuru County where he has set aside and enclosed one-acre of his land for FMNR. He did this in 2022 after being trained on the FMNR approach by World Vision through the Central Rift Farmer Managed Natural Regeneration Scale-Up Project (CRIFSUP). Funded by the Australian Government through the Australian NGO Cooperation Program (ANCP) , the project has trained 1,000 farmers across 4 counties (Baringo, Elgeyo Marakwet, Nakuru and West Pokot) in Kenya.

Isaac used to allow his livestock to freely graze on the farm. However, he claims that following the training, he realized how crucial it was to enclose and divide his land into cropland and forestland to ensure livelihood resilience and sustainability.

To diversify their sources of income as well as nutrition, Isaac grows sorghum, maize, vegetables among other crops. In addition to rearing chicken, he grows Boma Rhodes grass on his three-quarters of an acre, which he intends to store for future use as pasture or sell depending on demand.

Isaac reveals a tip they learned as children to make sure they had enough food to sustain them for a year following each harvest.

”I apply budgeting in food,” he explains,” Every member of my household is required to preserve a minimum of two and a half bags of the produce after harvesting. The two sacks are to make sure my family has food for the entire year, and the other half is to aid others in need or during an emergency.”

“FMNR is the cheapest way to restore our lands. It needs no water, is suitable for arid and semi-arid areas, does not need any expertise or technology and all you need to do is to take care of your land,” Isaac says.

His extensive knowledge and dedication to the FMNR practice has seen him train and motivate a remarkable 25 farmers in his village who are now actively practicing FMNR.

“I am glad to have trained so many people who are implementing FMNR. That gives me hope that my village will transform. People will no longer steal firewood from others’ homesteads because they’ll get their own from FMNR,” Isaac says.

The leafy well-managed trees in the homestead not only serve as a haven for chirping birds but also as wind breakers, a source of herbal medicine, prevent soil erosion and a source of shade for Isaac’s family, friends and livestock when it is scorching hot.

Lina claims that the most significant benefit of FMNR for her family has been reduced soil erosion and improved availability to firewood.

“When soil and crops are carried away by floods, there is no food,” she says, "We used to spend around 7 hours gathering firewood in the forest. You return home exhausted, unable to perform any further tasks, despite the fact that the bunch collected will only last three days before you have to return to the forest. Even children were unable to study after collecting firewood."

Lina says she now has more time to handle other household chores because firewood is readily available once the trees are pruned. Lina also has an improved energy-saving cookstove that conserves heat, uses less firewood and emits less smoke. Furthermore, the family may now save 400 KES (3.10 USD) that they occasionally spent on purchasing a bunch of firewood that was used up in seven days.

“Training communities on FMNR and the use of improved energy-saving cookstoves and other technologies ensures that there is less pressure on the trees regenerated in their farms. This is because the improved stoves require significantly less firewood compared to traditional modes of cooking. Additionally, there is reduced exposure to respiratory complications as the stoves emit relatively less smoke,” explains Mary Wambui, Project Officer and Environmental Specialist at CRIFSUP, World Vision Kenya.

”FMNR is about sustainability for future generations. When there are trees, there is increased soil fertility, improved soil structure, as well as high-yielding crops and livestock,” Isaac states with conviction.

Isaac is among several farmers in Nakuru County who have developed a positive mindset towards conserving the environment. This mindset change enables farmers to live in harmony with nature, caring for it and enabling them reap holistic benefits thus building their resilience to the impacts of climate change.

World Vision Kenya remains committed to restoring over 4 million hectares of degraded land in Kenya to address climate vulnerabilities that have a detrimental impact on children's and families' livelihoods.

By Hellen Owuor, Communications Specialist (CRIFSUP), World Vision Kenya